Lecture 3a - Cell Biology and the Organization of Multicellular Life #SC-214

This post initially appeared on Science Blogs

[This past fall, I taught a course at Emerson College called "Plagues and Pandemics." I'll be periodically posting the contents of my lectures and my experiences as a first-time college instructor]

One of the biggest challenges in organizing this class was figuring out how to incorporate readings into the class material. Since I wanted to give the students a firm grounding in evolution as a way to understand infectious disease, one of the required textbooks I assigned was Carl Zimmer's excellent introductory textbook The Tangled Bank.

Unfortunately, I felt I only had a couple of days to give the introduction to evolution, and I ended up loading the kids up with way too much reading. If I teach this course again, I think it would work much better to spread the discussion of evolution out over several class periods, but weave it in to the discussion of infectious diseases right from the start. As it was, I came back to evolution over and over again, and I think the students had a fairly firm understanding of it (at least in the context of disease) by the end, but I could have started out better I think.

The other assigned texbook was Laurie Garrett's 1995 book The Coming Plague, which is phenomenal, but which I also didn't use effectively. I only ended up assigning 3 chapters out of the 20 or more, though at least two or three times that many were relevant to various parts of the course. This book is written more like journalism than a textbook, and the students enjoyed the chapters that I assigned. I'll definitely use both of these books again, but I think I can use them better.

Lecture 3a (Readings: Zimmer - The Tangled Bank, chapters 4 and 6)

In the last lecture (part 1, part 2), I discussed the development of the two fundamental theories that underpin almost all of biology: evolution by natural selection and the gene theory of inheritance. These two advances of the 19th century were fused in the early 20th century into the modern synthesis (also sometimes called neo-Darwinism), and still govern how we think about biology today. With that as a backdrop, I'm going to step out of the history lesson a bit and talk about our current understanding of multicellular organisms, cell biology, and what we call the "central dogma."

Cells and their organization

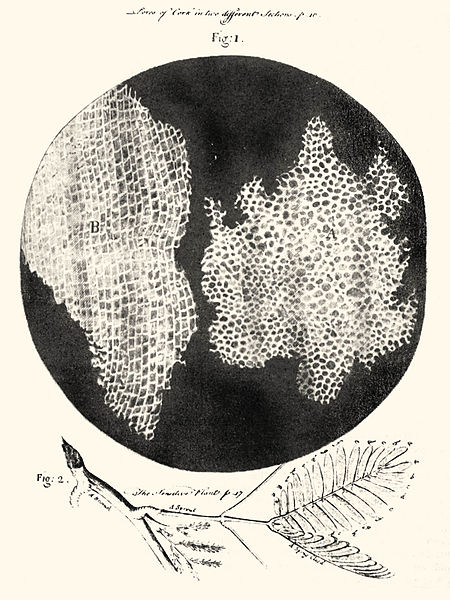

It might seem obvious, but we are not made up of a single thing. Our bodies are composed of trillions of distinct entities, each with its own boundary, its own metabolism, and it's own blueprint for life. In 1665, Robert Hooke observed cork under a microscope, and named these entities "cells" for their resemblance to the living quarters of monks (what Hooke was actually observing was the outline made by the hard walls of these plant cells left over after the cell had died). Hooke's drawing of cells in cork (source: wikipedia)

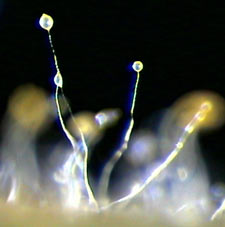

Many living things live as individual cells, and multicellular organisms run the gamut of complexity from dictyostelium, (a fungus that spends part of its life as a single cell, but then forms a multicellular structure to reproduce), to sponges (simple animals with less than 10 cell types), to people. Fruiting stalks of dictyostelium (click for source)

Why have many cells, instead of just one? Scientists still aren't sure exactly what selective pressures first drove unicellular organisms to team up with one another into a larger aggregate, but it's clear in hindsight that multicellularity caries many benefits. For one, when many cells team up together, some of them can specialize. A single-celled yeast has to know how to move, find food, collect the food, digest the food, keep itself protected from predators and parasites, find mates (if it's sexual) etc etc etc. By contrast, a hepatocyte (liver cell) in a mammal has only a few functions, and can leave the rest of those jobs to others. Because of this, that hepatocyte can be really good at its limited functions.

Multicellular organisms thus have many different cell types, from less than a dozen in a sponge, to hundreds or thousands of different types in a human. These cells may have a lot of different functions, or be highly specialized, or have no other function than to give rise to other cell types. In any case, these cells must be organized into larger structures in order to carry out their function, and to contribute to the larger organism.

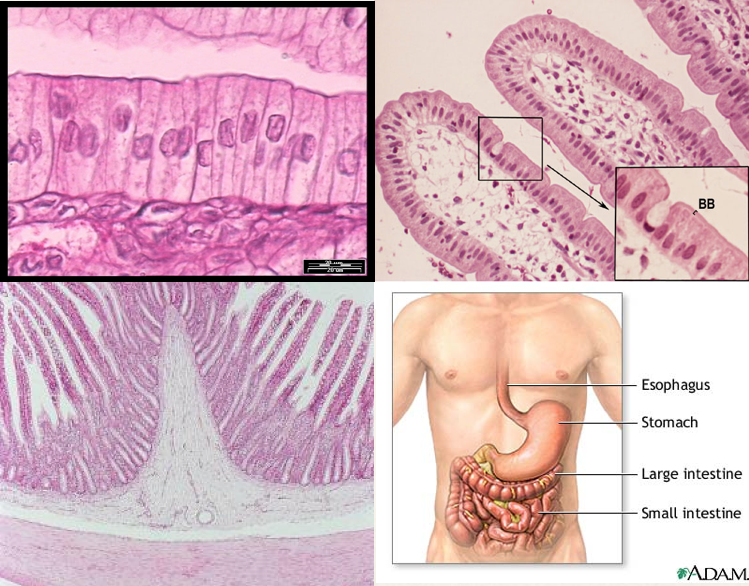

For instance, "columnar epithelial" cells line the inside of our gut, and function to provide a barrier, absorb nutrients, and secrete mucous to lubricate and protect from invading microbes. These cells are organized into a larger structure, or "tissue," that is comprised of several different cell types that all work together. The epithelial tissue is in turn organized with many other tissues (like smooth muscle), to form the "organ" of the small intestine. The small intestine is organized into an "organ system" - the digestive tract - along with the stomach, large intestine etc. Close up of columnar epithelial cells (TL), these cells organized into villi, surrounding the lamina propria (TR), a cross section of the small intestine, showing the epithelium (dark pink) over the lamina propria (white), and smooth muscle (light pink) (BL), and the small intestine along with other organs of the digestive tract.

Likewise, the nervous system is composed of the brain, spinal chord and peripheral nerves, all of which can be further subdivided into different tissues and cells etc. In this way, many individual cell types can be organized at various levels to comprise a complex, multicellular organism like a human.

But how do individual cells do their thing?

Intro to Cell Biology

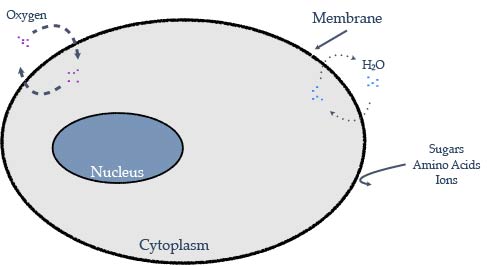

All* cells share a few basic requirements, and a few basic features. First, they need something to separate the outside of the cell from the inside. This is called the "plasma membrane," and is composed of a double layer of molecules that serve as a semi-permeable barrier. Imagine it like a chain-link fence surrounding a property - dogs and cats might be kept on one side or the other, but insects can pass back and forth without trouble. Actually, the membrane surrounding cells is much more selective, and prohibits movement based on more than just size, but the idea is the same.

But you wouldn't surround a property in a solid chain-link fence. Sometimes you want to allow things to pass from one side to the other that wouldn't fit through the fence. But you want to be able to control when, where, and how much goes in and out, so you build in gates and other portals. In the same way, cells have channels that can allow certain molecules to pass in one direction or the other in a controlled way, or pumps that actively push molecules to one side or the other.

Cells also need ways to perceive the outside environment. Usually, this is accomplished by things called "receptors," which are basically sensors that span the membrane. These receptors can perceive the environment on the outside of a cell and communicate that information to the inside of the cell. We'll leave receptors as a black box for now, and get back to how they work in a later lecture.

The final basic feature that I want to talk about is the genetic material. This is the blueprint that every cell carries and that provides all of the instructions for how a cell behaves. You've probably heard of genes and DNA, but to go forward in this class, we need to put those things in context. But to understand what genes do, you first need to understand what proteins do.

Proteins do the work of the cell.

Proteins do everything (just about)! From carrying out chemical reactions, to communication between cells, to basic structural support, different proteins are responsible for almost every function in a cell. Those channels and pumps I mentioned above are proteins. If you're thinking of protein from a dietary perspective, the reason that meat tends to be high in protein is because it comes from muscle, and muscle contains high quantities of proteins that are able to contract and exert mechanical force. In the cell factory, every screw, gear and conveyer belt, and even the workers that operate the machinery are proteins.

Proteins can be quite large as molecules go, but at their core they are just long chains of smaller molecules called "amino acids." There are 20 different types of amino acids, and the order in which they are linked together influences their shape. Imagine a chain where each link is coated in either fuzzy or hooked velcro, or a positive or negative magnet. you could lay that chain out in a line, but if you put it in a box and shook it, what you pulled out of the box would be some tangled mess, but it would have some defined shape - each part of the chain may interact with other parts, repelling each other like two positive magnets, or sticking together like velcro or opposite-charged magnets.

In a long chain of amino acids, there are a lot of different types of interactions (not only 4 as in the example above). The order of those amino acids, as with the order of magnets and velcro, determines the final shape that the chain folds into, and that final shape determines the function of the protein. So how to determine that order? That's where genes come in.

But seeing as how this post is already super long, I'm going to put the explanation of how genes become proteins in a separate post... coming soon (I learned how to use Adobe Illustrator just to make the diagrams, it's going to be awesome!).

Stay tuned!

Any time I use categorical statements like "All cells..." or "Any time I..." when talking about biology, there's a good chance that there are a couple of examples that run contrary to the statement I'm about to make. For instance, even though all cells must have had genetic material at some point, red blood cells jettison their nucleus during development and carry out their function quite happy without any genomic DNA.

Post Images

Missing image: Image at /files/webeasties/files/2013/02/450px-RobertHookeMicrographia1665.jpg | /files/webeasties/files/2013/02/450px-RobertHookeMicrographia1665.jpg

Missing image: Image at /files/webeasties/files/2013/02/Screen-Shot-2013-02-06-at-9.03.38-PM.png | /files/webeasties/files/2013/02/Screen-Shot-2013-02-06-at-9.03.38-PM.png

Missing image: Image at /files/webeasties/files/2013/02/Cell-Membrane.jpg | /files/webeasties/files/2013/02/Cell-Membrane.jpg