Rock Climbing, Fat Fingers and Arthritis

This post initially appeared on Science Blogs

In any physical activity, there is always the risk of acute injury - cuts, scrapes, bruises, and even broken bones are often par for the course. For some extreme sports like rock climbing, where you voluntarily drag your body hundreds of feet into the air on the side of a sheer rock wall, athletes are even willing to risk death.

Me following up a 5.9 in Rumney, NH... probably not risking death.

Those acute sports injuries can sometimes grab headlines, but people are increasingly becoming aware of the long-term consequences of physical stress on the body. Football and hokey players can suffer from memory loss and depression as a result of swelling in the brain associated with repeated concussions, tennis players often get stress fractures on their spine (not to mention the aptly named tennis elbow), and many, if not all sports are thought to increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis - in which the cartilage in your joints breaks down, allowing bone to rub against bone and inducing inflammation.

This increased risk of arthritis is of particular concern for climbers - there are a lot of joints in the hands, and climbing tweaks them in all kinds of ways.

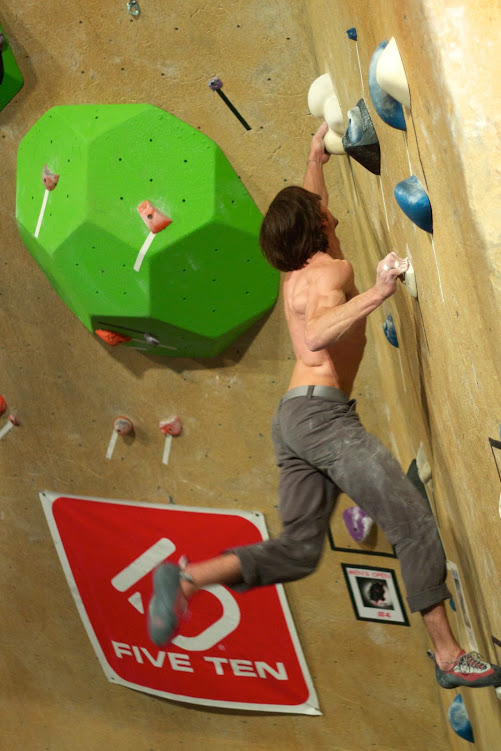

I'm not sure who this climber is, but he was competing in the Dark Horse finals in Feb 2012

It's sort of accepted wisdom in climbing circles, and I never questioned whether or not it was true until a friend of mine told me that actually, climbers have a decreased risk of arthritis. So I decided to do some digging.

First off, let's take a look at the increased risk of osteoarthritis for sports in general - it turns out, it's not that simple:

Participation in sports that cause minimal joint impact and torsional loading by people with normal joints and neuromuscular function may cause osteophyte [bone spur -kb] formation, but it has minimal, if any, effect on the risk of osteoarthritis. In contrast, participation in sports that subject joints to high levels of impact and torsional loading increases the risk of injury-induced joint degeneration. People with abnormal joint anatomy or alignment, previous joint injury or surgery, osteoarthritis, joint instability, articular surface incongruity or dysplasia, disturbances of joint or muscle innervation, or inadequate muscle strength have increased risk of joint damage during participation in athletics.

Let me translate: if you're not putting too much strain on your joints, a bit of sport isn't going to increase your risk. But sports that "subject joints to high levels of impact and torsional loading," does increase your risk. If hanging your entire body weight from two fingers doesn't count as high torsional loading, I don't know what does.

The move after this involves doing a one-armed pull up while holding onto that two-finger pocket

So then was my friend completely full of crap? It turns out, there have been a several medical studies on this very topic, and they offer up conflicting results. One study published in 2006 examined the hands of 26 recreational rock climbers and compared them to the hands of non-climbers. As you might expect, the hands of the climbers were much stronger than the hands of the non-climbers, and the climbers even had thicker bones, which the authors suggest might indicate that the bone is actively remodeled to make it more powerful. However, these researchers found no indication that the climbers had an increased risk for osteoarthritis.

By contrast, a study published 2 years earlier examined 19 members of the German Junior National Climbing Team (professionals), 18 recreational climbers and 12 non-climbers - these researchers determined that the climbers were at increased risk, since one member of each of the climbing groups had early signs of osteoarthritis and none of the non-climbers did. Another study published in 2011 supports this conclusion, showing that adult male sport climbers regularly get bone spurs and show significantly increased signs of osteoarthritis.

Finally, the study that I think has the best methodology, followed the 10 members of the German Junior National Team, 10 recreational climbers and 12 non-climbers over the course of 5 years. Their conclusion:

Intensive training and climbing leads to adaptive reactions such as cortical hypertrophy and broadened joint bases in the fingers. Nevertheless, osteoarthrotic changes are rare in young climbers.

Unfortunately, all of these studies suffer from the same basic flaw - small numbers of test subjects. All of the bone-thickness stuff is pretty consistant - climbers' hands are structurally different - but the signs of osteoarthritis are so rare that they could have arisen by chance. Furthermore, all of the athletes in these studies were fairly young, and age could reveal problems (or lack thereof) that might not be apparent in the younger athletes.

Based on what we know about sports-related stress and osteoarthritis, it's reasonable to assume that there would be similar effects on the hands of climbers. But seeing as how we evolved from tree-climbing ancestors, it's also reasonable to predict that our hands might be better able to adapt to these stressors better than the stressors of swinging a racket (as far as I know, there's no evolutionary precedent for tennis). In fact, I don't even think it would have been unreasonable to predict that the increased strength attained from climbing might help you ward off osteoarthritis, though none of the studies I found suggested that (if any of you know the study my friend was referring to, please let me know in the comments). This type of intese climbing really started increasing in popularity about 30 years ago, so the first crop of climbers is starting to approach retirement age. It will be interesting to see if anyone begins to study these old timers to see how their hands and other joints are keeping up. As with so many things in science, the best I can say right now is that more research is needed to draw solid conclusions.

Well, I might be able to draw one conclusion: climbing is awesome!

Daniel Woods - Dark Horse 2013 Champion, on route 3 of the Men's finals

[All photos in this post were taken by me* and are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License]

*Obviously, the picture of me wasn't taken by me, but it's still mine!